architecture

archive

Microservice boundaries are logical not physical

by Bob

Sun Feb 28 2016

My problem with the Microservices movement is that people are applying the lessons of micro-services without having first learned the lessons of service-oriented architecture. This leads to confusion and accidental complexity.

two micro service depend[ing] on the same data storage ... is a "No No" as it can introduce lots of other complexity. But what happens if one of the micro-service is only read only?

So here is the situation, one micro service will be an internal tool which is doing some heavy lifting and then persisting the data in the data base. And another micro-service will be a REST interface which will just read the data. Is it fine if some one use same database for both of the service?

Pro-tip: if you answered "No", you're doing it wrong. The kicker: If you answered "yes", you're also wrong.

To understand why, we first need to go back to basics and ask a very simple question: What is a service? Mulesoft pithily summarise:

A service is a self-contained unit of software that performs a specific task... Because the interface of a service is separate from its implementation, a service provider can execute a request without the service consumer knowing how it does so.

This is true, but it skips over the most important thing about services, which is that Services are business concerns, not a technical detail. The first key idea in the Mulesoft quote is that services are based on contracts. If you send me data A, B, C then I will return data X, Y, Z. The second key idea is that implementation is not relevant so long as you implement the contract.

The linked reddit thread is full of well-intended advice. You should NEVER share a database with multiple services. Sharing databases is akin to sharing needles; it might seem convenient now, but you'll pay for it in due course.

The question is wrong, however, because it assumes that the "heavy lifting" component and the "REST interface" are different services.

In adopting microservices, most people have focused on small deployable units (a microservice should be small enough that you can rewrite it in a sprint!!) rather than on small contracts (a microservice should be small enough that you can describe it in one sentence, without using the words 'but' or 'then').

wut?

Let's pretend that our redditor is building a system for modelling an industrial process. He works for a large enterprise who have an energy-intensive process for making widgets. In order to optimise their costs, the company bids for electricity on the open market. This allows them to make savings when demand is low, but costs them more when electrical demand is high. It takes three units of electricity to make one widget, which means that the profit margin on any given widget depends on the cost of electricity when that widget was produced.

The CEO of Acme Widgets inc. wants to see realtime information on electricity expenditure.

Our plucky redditor therefore sets forth to build the Widget Profit Reporting Service.

What does this service do? What is the contract?

- Given data on the spot price of electricity through the day

- Given data on widget production through the day

- I will give you the total cost of electricity in widget production.

This is very clearly a contract that is expressed in business requirements, not technical requirements: it doesn't matter how many processes you run, so long as your CEO sees accurate numbers.

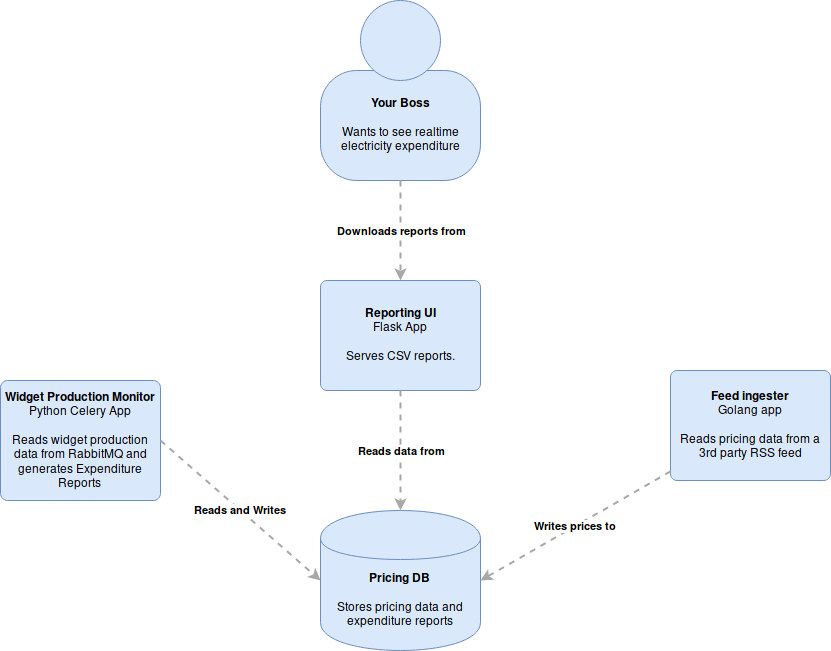

The above diagram shows one possible implementation. Pricing data is downloaded from an RSS feed. In order to meet the soft-realtime requirement, we accept production information over a Celery/RabbitMQ queue. Then we run a rules engine to determine what we paid and save the result into a Postgres database.

The CEO can access that data through a web-browser at any time. Because he's only accessing the results of the calculation, we can serve data really quickly, and he can send it to all the board members whenever he likes. This is the basic idea behind CQRS.

Note that we have three separate deployable applications, though: a celery consumer that reads production data, a go app that reads pricing info, and a Flask application that serves our data to the CEO. Since all of these applications are fulfilling the same contract, they are part of the same service, and because they are part of the same service they can talk to the same database.

If we take away any one of these components, we can no longer fulfil our contract to the CEO. As a result, we are content to deploy all three components together whenever the database changes.

If the codebase is small enough, we can still call this a microservice. It is not a monolith, it is not breaking any rules: (Micro)service boundaries are logical (aligned with business requirements) and not physical (aligned with processes or machines).